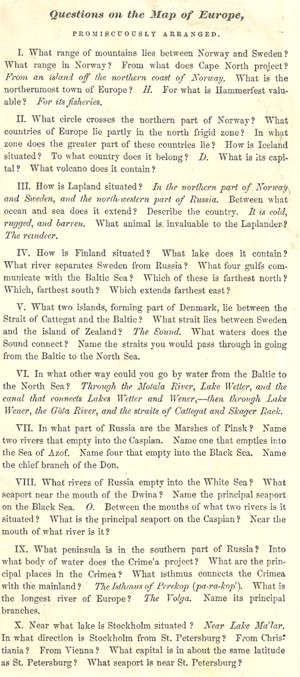

This was on the back of a map that arrived today:

Although it looks quite forbidding, actually it's more to do with reading maps than learning the names of Swedish lakes. Yes, you may well come away knowing that the capital of Russia is St. Petersburg and the capital of Norway is Christiania, but what you're actually being taught is one step removed from this: you learn where countries are, what a gulf is, that rivers run to the sea, that geographical boundaries can form country boundaries, ...

In other words, you learn things indirectly as well as directly. If you're trying to find the name of the circle that crosses Norway, you're going to get the answer quicker if you know where Norway is. The questions give you goals, and you'll pick things up while achieving these goals because this will make it easier to achieve other goals. It's the things you pick up that are really being taught, though, not the answers to the questions. The questions are just there to motivate you.

This is how educational games work, too. Games are more fun than looking up facts that are of marginal use at best, but the basic principle is the same: decide what you want to teach, then set goals to do something that requires the acquisition of expertise in that area.

These days, schools don't teach "boring facts" such as dates. This is because they're, well, boring, and because children can never remember them anyway. What's been lost, though, is the understanding that dates weren't taught for their own sake, they were taught because of what you had to know to make sense of them. People weren't being taught dates, they were being taught history; dates were just the front line — the stuff you didn't need to know, but which through their manipulation taught you what you did need to know. Eventually, though, teachers lost sight of how this worked and thought that the dates themselves were important; when this happened, the educational use of (in this case) dates vanished.

We can't teach boring facts such as dates now, because people recognise that they aren't much use in and of themselves. However, this means we try to teach the interesting stuff as plain facts instead — which makes those boring in turn. This is why educational games hold such promise: they can give people reasons to want to learn things. All that's stopping them is the persistent belief that their direct goals should be "educational" — ie. that players should not be given goals that are not immediately relevant to what they are supposed to be learning. Yet, as the above set of questions shows, even when they are directly relevant, they aren't what the children learn. They're just a smokescreen to make people think they or their children were being taught something important when actually they were being taught something else (which actually was important).

Oh well, it'll all come right eventually...

Unfortunately, the map I bought was of central Europe, so most of Scandinavia is missing. I can't therefore answer the questions from it, as they were related to a different map. I can, however, tell you that Lemberg is on the River Bug.